From trauma-informed to asset-informed care in early childhood

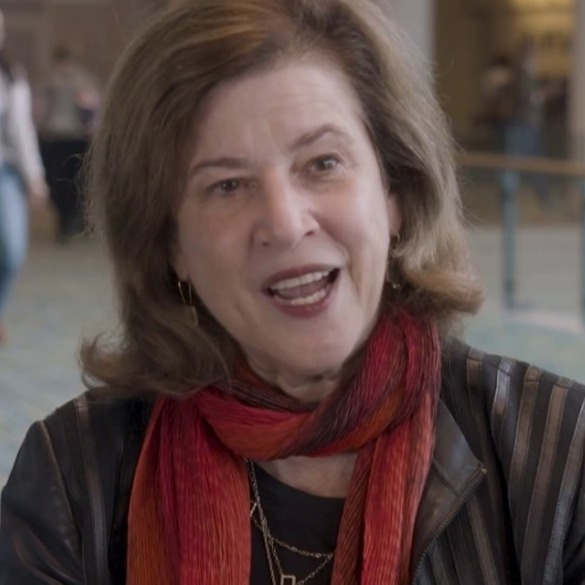

- By Ellen Galinsky, Bezos Family Foundation Chief Science Officer and Founder/Executive Director of Mind in the Making

- Latest Research

The focus on “toxic stress,” ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences), and trauma-informed care have been game-changers in the field of early childhood development. They have helped us recognize the symptoms of trauma, provide appropriate assistance to children, and understand that prolonged adversity in the absence of nurturing relationships can derail a child’s healthy development. Just look at the media’s and the public’s reaction to the impact of separating families at our southern border or at Florida’s statewide trauma-informed initiative as compelling examples of how these concepts have led to change.

So, given these positive results, it may be a surprise that I propose expanding beyond these problem-focused, trauma-laced concepts to narratives and solutions that are rooted in children’s and families’ assets. Here’s my journey—why I have come to these conclusions—as well as examples of solutions.

KEY POINT I: ADVERSITY IS NOT DESTINY.

Not too long after the words “toxic stress” were introduced by the Harvard Center on the Developing Child in 2005, our team at Mind in the Making, now a program of the Bezos Family Foundation focused on the science of children’s learning, was conducting a training program for educators. One of the participants wanted to discuss what differentiates positive stress from tolerable stress from toxic stress.

We knew that these words make complex scientific concepts understandable—they enable policymakers and the public at large to grasp how early and ongoing adversity activates biological stress response systems of a child’s developing brain, immune system, metabolic regulatory systems, and cardiovascular system.

During this discussion, a well-known educator sounded an alarm. Toxic stress, she said, doesn’t just affect the children we work with. It affects their parents, their teachers, and many of the educators in this room, including herself. Her voice full of emotion, she said that she would never use the words “toxic stress” with parents or educators because “toxic stress—well, it sounds so fatal.”

To be clear, the Harvard Center continues to emphasize the “resilience” of the developing child—the brain’s and the body’s ability to manage and recover from severe stress, as well as how caring relationships can act as an antidote to stress. Nonetheless, I’ve found that I have to make this point repeatedly in discussions of adversity, because this language may imply that toxic stress could, in fact, be fatal. My mantra has become “adversity is not destiny.”

KEY POINT 2: STEREOTYPING CAN SERIOUSLY HARM CHILDREN.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines ACEs as “all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under the age of 18.” The concept originated from a large CDC-Kaiser Permanente study that took place from 1995-1997 in which participants received questions about exposure to forms of household dysfunction prior to turning 18.

In more recent replications of the original study, researchers found more than two-thirds of participants experienced at least one ACE and one in five experienced three or more. The more ACEs an individual experienced before 18, the more likely s/he were to suffer from substance abuse, depression, health problems, or attempt suicide. A 2018 Child Trends’ study found that 45 percent of children in the U.S. have experienced at least one ACE, and one in nine children nationally has experienced three or more ACEs.

Knowing that a child is in a family where there is divorce or a violent community often leads people to make negative assumptions about children. I have been in too many meetings where participants assumed that children with disruptive behavior or in low-income communities have high ACE scores—and maybe even small brains. These children are being stereotyped, and stereotypes can harm children, lead to discrimination, and even become self-fulfilling prophecies. Again, words and the assumptions they conjure matter. We should not make assumptions just because children live in poverty or have experienced adversity.

KEY POINT 3: PEOPLE WHO HAVE EXPERIENCED TRAUMA SHOULD NOT BE “DEFINED” BY THEIR TRAUMA.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network has been a powerful and effective proponent of creating trauma-informed programs and systems that “infuse and sustain trauma awareness, knowledge, and skills into their organizational cultures, practices, and policies.” Their mission is to facilitate the safety and recovery of every child and family so they can thrive.

It was in a conducting a healing circle for African-American youth that led Shawn Ginwright of San Francisco State University to the conclusion that we need to move beyond trauma-informed care to healing-centered engagement. As he writes:

All of them had experienced some form of trauma ranging from sexual abuse, violence, homelessness, abandonment, or all of the above. During one of our sessions, I explained the impact of stress and trauma on brain development and how trauma can influence emotional health. As I was explaining, one of the young men in the group named Marcus abruptly stopped me and said, ‘I am more than what happened to me. I’m not just my trauma.’

KEY POINT 4: WE NEED TO BUILD ON CHILDREN’S AND FAMILIES’ ASSETS.

Without a doubt, the emphasis on toxic stress, ACEs, and trauma-informed care has been beneficial. Teachers who have received ACEs training are less likely to assume that children who act out are “willful” or “bad” and to expel children from school for poor behavior. School officials with similar training have begun listening to children more and helping them learn to manage their behavior through practices like mindfulness. These changes are worth their weight in gold.

But, it’s time to shift beyond a focus on these trauma-laced concepts. As child and adversity expert Philip Fisher of the University of Oregon said, “focusing on trauma is the starting line, not the finish line.” Successful interventions are asset-based, focusing and expanding on what children and adults are already doing that’s right. Here are two examples of this approach:

First, Alicia Lieberman of the University of California, San Francisco developed a program called Attachment Vitamins, a 10-week course helping parents and caregivers of children from birth through age 5 repair the impact of chronic stress and trauma by promoting emotional attunement, mindfulness, and executive and reflective functioning. Lieberman and her colleagues describe how they set the tone for the first session of this intervention.

The first question asked of parents is, “Tell me what you love most about your child.” By asking parents what they love most about their child, the facilitators tell parents that they assume they are, in fact, loving parents…It is a strength-based approach that places the focus on the parent’s primary motivation for the class—the relationship with the child.

Throughout the program, parents share “moments of connection” with their child. Parents are encouraged to choose specific moments so they know the strengths of their relationships and engage in more connection opportunities, even as they probe and address the impact of trauma on their family. Reprinted from The Brookings Institution